After looking back at some of the pictures we had taken of Engrish during our time in Japan, we came across an unused stash of many weird store names from MYLORD, a large shopping complex located within the Shinjuku station. According to their website, the name MYLORD was taken from the old English greeting used towards people of higher status. However, what struck us as really odd was the seemingly random nature of the store names, which incorporated odd punctuation, irregular capitalization and fonts, and strange word choices that did not give much information as to what kind of stores they were.

Thus, for this week, we decided to investigate the opinions of native Japanese students regarding these store names, and whether they, like us, found them odd and humorous, or perfectly normal names. Our interviewees (a.k.a. guinea pigs) for the week: Konomi, Mi-chan, and Fumiya, who graciously gave up some of their time to answer our questions (credit goes to Abby for giving us the idea to do a questionnaire in her contribution to our blog).

The following MYLORD store names were used in the interview:

E hyphen world gallery

RNA MEDIA

LOCK YOUR HEARTS

HYSTERIC GLAMOUR

LIPSTAR

Rid.dle... from a.g.plus

as know as de base

X-girl

mysty woman

JEANASIS

LEMONTREE COFFRET

Crisp

gaminerie

LOWRYS FARM

cactus ..cepo.

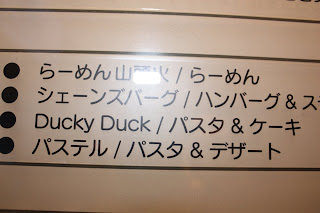

Ducky Duck/パスタ&ケーキ

leap lippin

LaZY SwaN

Dip Drops

POU DOU DOU VINGT-TROIS

Earth music&ecology

LAZY SUSAN

ODAKYU FLORIST Delicious

unlogical opinion

AGNET.H/L

iro-mi-ne by ITS' DEMO

To further our findings, we decided to also get the opinions of our interviewees on names of stores found in Market Mall back in Calgary. To that end, we decided on the following list of names for comparison:

The O Zone

Things Engraved

The Total Look

Twisted Goods

Vireo

Hot Gossip

iviwa athletica

L'Occitane

Please Mum

RW & Co.

TABI

Skoah

1. What are your thoughts regarding the Japanese store names? Do they sound cool or appealing? Do they sound awkward? Are there any reasons why you think this?

Konomi didn’t find the names funny/strange; rather, she noted that the names sounded very normal, while we found the names to be strange and a mish-mash of gibberish. However, she also noted that the names were not very meaningful, a common theme amongst many Japanese stores, where the purpose of the English name is to merely sound (and look) cool, rather than be informative. Like us, she said that Japanese people really didn’t interpret any meaning from the names; most people simply take them at face value.

Mi-chan was a special case because his major is English, and thus has a relatively firm grasp of the language. Like Konomi, he commented that Japanese people find these names to be relatively normal, and tend not to pay attention to the meaning behind store names, mostly because they can’t translate or understand the English name, and so only pay attention to the visual appeal of the name. This may explain why some stores use awkward punctuation and word choices, such as Rid.dle... from a.g.plus, Ducky Duck, and LaZY SwaN; while we may find the random use of periods and capitalizations odd, it’s relatively obvious that they would offer a greater visual appeal not seen in Western storm names. Ducky Duck is a particularly notable example of lack of meaning in Japanese store names—contrary to our initial belief, it is actually a pasta and pizza restaurant that serves no duck whatsoever. Here, the name derives its appeal merely from its sound.

In his personal opinion, Mi-chan didn’t find the names appealing or cool, mostly because he is an English major and can clearly see the lack of meaning in the names. As well, Fumiya thought Japanese store names lacked meaning, similar to what Konomi and Mi-chan thought.

2. What are your thoughts regarding the Canadian store names? Do they sound cool or appealing? Do they sound awkward? Are there any reasons why you think this?

All three interviewees thought that the Canadian store names had more meaning than the Japanese names; in particular, Konomi found Things Engraved to be rather informative. However, Mi-chan noted that these meanings did not seem very deep at all, and when asked whether he found them funny or awkward in the same manner as we found Japanese store names funny and awkward, he merely said that he was neutral towards them and didn’t find them particularly funny or awkward when compared to the Japanese store names. Fumiya also thought that the Canadian store names were more serious compared to the Japanese store names.

3. If you had different feelings or thoughts when you read the Japanese and Canadian store names, could you explain how you found them different, and why you had different feelings?

In all cases, each person had a different feeling when they read the Japanese store names in comparison to the Canadian store names. However, there was an interesting contrast in how they found the names different and why they elicited different reactions within them. Konomi felt that the Japanese store names were simpler than the Canadian store names, while Mi-chan though that the Japanese store names were harder to read than their Canadian counterparts. Both, however, found the Canadian names more appealing due to the fact that they used correct English, which gave a totally different feeling in Konomi’s opinion. For Mi-chan, the use of correct English helped him understand and read the store names more easily. In Mi-chan’s opinion, however, other Japanese people would find the complicated Japanese store names more appealing than the Canadian names due to the fact that they use unorthodox English, which seems cooler.

For us, we felt the Japanese names gave a totally different feeling compared to the Canadian names, mostly because we couldn’t understand the names, nor get any sort of meaning out of the names (for instance, Carolynn thought LOWRYS FARM was a pet shop of some sort when it was a clothing store, while Alex, as a biology major, thought RNA MEDIA was very humorous because RNA stands for ribonucleic acid in biology). In this sense, we related to Mi-chan’s point of view the best.

4. Which 3 Japanese store names do you find the most appealing? The most awkward/confusing/funny?

Konomi found X-girl, RNA Media, and Earth music&ecology the most appealing, whereas Ducky Duck, Crisp, and POU DOU DOU VINGT-TROIS made Mi-chan’s top 3 most appealing list. For Konomi, Earth music&ecology sounded cool, whereas for Mi-chan, Ducky Duck was merely funny, Crisp was odd, and POU DOU DOU VINGT-TROIS was appealing because he couldn’t understand what it was supposed to mean.

For the most awkward names, Rid.dle... from a.g.plus, mysty woman, and POU DOU DOU VINGT-TROIS made Konomi’s top 3, while Mi-chan chose Earth music&ecology and as know as de base. It was interesting to see that Mi-chan and Konomi had opposite opinions on Earth music&ecology and POU DOU DOU VINGT-TROIS. Unlike Konomi, Mi-chan found the use of “ecology” in Earth music&ecology strange and humorous given the fact that the store sold clothes. For Konomi, Rid.dle... from a.g.plus was awkward given the difficulty in reading the name.

5. Which 3 Canadian store names do you find the most appealing? The most awkward/confusing/funny?

Hot Gossip made the top 3 for both Konomi and Mi-chan, with Konomi rounding off her list with RW & Co. and Skoah and Mi-chan with Please Mum and The Total Look. Both thought Hot Gossip sounded cool, while Mi-chan chose Please Mum because he found it humorous.

For the most awkward names, Mi-chan chose Skoah, RW & Co. and Vireo, whereas Konomi chose The O Zone and The Total Look. Here, we again found differing opinions between the most awkward and most appealing names in the cases of Skoah, The Total Look, and RW & Co. From our perspective, we found some of the Canadian names rather uninformative and couldn`t really tell whether or not the names had any specific meaning; thus, while Japanese store names may seem odd to us in their reliance on visual and aural appeal, the same can be said of Canadians store names which, in retrospect, could very well be indistinguishable from some Japanese store names (e.g. Hot Gossip or Skoah). As an aside, Mi-chan and Konomi both found TABI to be very interesting as たび in Japanese means “trip” (in the sense of travel).

Conclusion

While Westerners would likely find the Engrish in Japanese store names to be random and incomprehensible, the Japanese don`t see anything particularly odd in the names. Our interviewees shared a common opinion with us when they saw no specific meaning in the store names, and found Canadian names more meaningful and appealing. The interviews also re-emphasized a previous point made in earlier posts: that the use of English in aspects of Japanese society such as marketing tends to focus purely on the visual appeal of the English rather than any particular meaning.

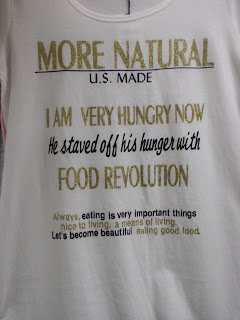

While this Engrish is fodder for humour from a Western perspective, the West is by no means guiltless in the misuse of other languages, including Japanese. This is evident in an example Konomi brought up in regards to a comparison between our interpretation of Engrish as Westerners and the Japanese perspective on the use of kanji in Western society—namely, through t-shirts. Just as Japanese stores use English in order to sound cool, Westerners sometimes buy t-shirts or other paraphernalia containing cool-looking kanji merely for style and appeal. However, we don’t think about the meaning of the kanji, and Konomi noted that Japanese people find it odd when they see Westerners with kanji t-shirts that make absolutely no sense, just as Westerners find English on store names weird. Thus, language misuse may be more universal than we previously believed.

By Carolynn and Alex