With our program coming to an end, we decided to do a review of some of the Engrish we had collected over the past few weeks. This week, we decided to interview some of the local and foreign exchange students of Senshu University. Because we were curious about whether or not other people perceive Engrish as we do (that it is absolutely hilarious), we chose three of our favourite samples of Engrish from three categories (T-shirts, Products, and Signs) and asked the following questions:

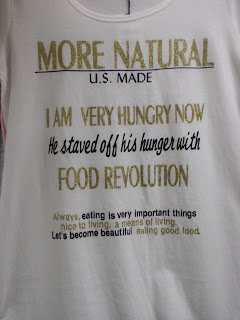

T-shirts

Would you want to buy this shirt? Why?

(For Canadian students) If you wore this shirt in Canada, what do you think people would think?

Products

Would you be more inclined to buy this product if the packaging was purely in Japanese Or would you still prefer this Engrish version? Why?

What would you think if this product was being sold in a Canadian store?

Signs

If you saw Engrish on a Japanese restaurant versus a Western style restaurant, do your feelings differ between the two?

Would you ever go into an Engrish establishment simply because it has Engrish? Why or why not?

What’s your opinion of the sign?

Our basis for asking these questions was to look into how Engrish was perceived by both Westerners and Japanese people and to see how their perceptions differ. For instance, some Westerners may buy t-shirts or other products with Engrish simply because they are humourous, whereas Japanese people may not have such inclinations. Additionally, we were curious whether or not Engrish affects people’s perceptions about the quality of a product (for instance, does bad Engrish give the impression of poor quality?). In addition, our panel was asked to rate the Engrish samples from 1-10 (1 being boring, 10 being absolutely hilarious). We received some interesting responses, so without further ado, let’s introduce our panel.

Alex “Masuda” Henderson, Ovid “The Crusher” Kwok, and あい (Ai)

And now, their responses.

T-shirts

Our panel had differing opinions on our t-shirt samples. While Alex and Ovid both expressed an interest in purchasing some, if not all, of the t-shirts we showed them, Ai’s feelings were the opposite. Her reason was that she could read and understand the awkward English on the shirt, and would feel shy to wear the shirt in public. However, she did note that if she wore these shirts, people in Japan would probably focus solely on the typography and style of the words, and not so much the meaning. In this regard, she mentioned that if she were to buy a shirt, she would prefer the “Adventure Family” or “Let’s stop the order” shirts because their texts are very small and their words are longer (respectively), which would put less focus on the meaning of the words and more on the shirt’s style.

Alex and Ovid, on the other hand, found some of the shirts quite funny and would purchase them purely for humour. However, they noted that if they were to wear the shirts in Japan, people would not probably give any special attention to the shirt, given that they are so common in Japan. Ai gave the same opinion; it seems that in Japan, at least, such Engrish on t-shirts is prevalent enough that Japanese people don’t give them a second thought. However, we were curious as to whether Alex and Ovid thought Canadians would find these shirts weird if they wore them in Canada. While Alex thought that Canadians would think the shirt would be hilarious, or that she was “special” if she wore it, Ovid thought that the response from Canadians wouldn’t differ that much from Japanese people. Our initial thought was that because Canadians would easily see the errors in the English, they may find the shirt weird and thus get a different impression of the person wearing it than if that person were wearing a normal shirt.

The final ratings for the shirts (Alex, Ovid, and Ai’s scores out of 10, respectively)

Food Revolution: 7, 8.5, 8

Let’s stop the order thinking: 6, 9, 5

Adventure Family: 8, 5, 5

Products

Our initial hypothesis was that people may get a different impression about a product depending on whether it had Japanese on it or funny Engrish. For the Geraid hair wax, the Canadians on our panel seemed to agree with us. Alex mentioned that if the wax was found in Canada, people would probably think that it would be of lower quality compared to other products, while Ovid noted that people would think it was a no-name brand and probably wouldn’t buy it. Another common theme in their opinions was buying products like Foot Pee! purely as a joke, and the fact that the Engrish on these products made their functions confusing. For instance, both Alex and Ovid wondered why on Earth you would use the Geraid hair wax for your skin and hair, as is suggested on the packaging; additionally, neither had any idea what the Foot Pee! was used for).

Ai, on the other hand, said she would prefer purchasing a Japanese version of the Geraid hair wax and callus remover rather than buying the ones shown with Engrish. For her, the Japanese version would seem more reliable, partly because she doesn’t understand the English on the product very well. While our previous posts involving interviews with Japanese students have reported that Engrish on Japanese products is used mainly to look good or act stylistically, Ai’s feedback seems to suggest that the presence of English on certain products is not enough to sway Japanese consumers from purchasing a certain product. In other words, looks alone do not sell.

While speaking of looks and the use of English to make products more appealing, Ai gave some interesting insight on the Foot Pee! product. Apparently, the exclamation mark is supposed to double as a lowercase “L”, so that the name actually reads, “Foot Peel!” The product is actually like a face mask, except for your feet: after you put it on and peel it off, your feet should be smooth. Thus, this product is a classic example of the stylistic use of English in Japan, and the (seemingly unintended) humour that can result.

With that said, here are the panellists’ scores for the above Engrish in products (Alex, Ovid, and Ai’s scores out of 10, respectively):

Geraid hair wax: 7 5 10

Foot Pee!: 9 8 10

Callus remover: 7 3 2

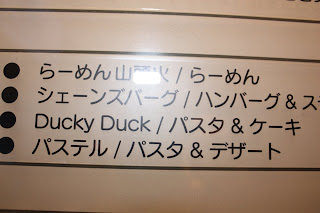

Signs

Our Engrish samples in this category came from department stores and a restaurant. In the case of the restaurant, we were interested to see whether or not people would perceive Engrish in Japanese restaurants differently from Engrish in Western-themed restaurants (that is, do people have the expectation that Western-themed restaurants would have better English in signs, and thus would be more critical or find more humour if the restaurant had Engrish in it?). Again, the use of “Pee” was found—this time, in a sign for a wine bar. When asked whether they would have differing opinions on Engrish in Japanese versus Western-themed restaurants, Alex and Ai answered no, and would probably have the same reaction to both. In Ai’s case, she wouldn’t think much of the Engrish—she would just assume it’s a normal restaurant name. However, Ovid thought that Western-style restaurants should probably have proper English, while Engrish on Japanese restaurants is not as unexpected. In addition, both Ovid and Alex noted that they would probably go into an establishment solely because of its Engrish for humour’s sake. In this sense, the Western perspective on Engrish becomes clear: it’s very funny—sometimes so funny that you just have to go into the restaurant or buy the product that has Engrish on it just so you can say that you did. By contrast, Ai noted that she would not go into an establishment solely because it had English on it, which again shows that the supposedly cool use of English may not be enough of a selling point to attract Japanese customers.

The second picture, which had a sign reading, “I really don’t know how to apologize to you. Please move to other cash registers,” elicited some interesting observations. As Alex nicely put it, the Engrish seems to be a translation of a perfectly normal Japanese phrase that can’t be translated literally into English without sounding unusual and funny. The inherent message is obvious: the cash register is closed, and the cashier is asking the customer to use a different register. However, this Engrish acts as a typical example of the cultural differences between Japan and Canada. In Japan, where manners and respect are highly regarded, it is extremely important to speak humbly, which often leads to very indirect, roundabout conversations or explanations. This cultural aspect is clearly evident in the Engrish here: rather than simply saying the register is closed, the sign emphasizes respect towards the customer in its apology and the often indirect style of communication found in Japan that carries a very humble tone.

When Ai saw this sign, she did not see anything unusual about it; in fact, she found it rather interesting that we saw it as humourous, whereas she wouldn’t have paid any specific attention to it. The same applied for the last sign we showed our panellists, which asked customers to purchase only one item per person. Here, the humour derives from the choppy writing and odd grammar, and while Alex and Ovid gave relatively high scores for this sign, Ai only gave a score of 2.

The final scores for the signs category: (Alex, Ovid, and Ai’s scores out of 10, respectively):

Pee Wine Bar: (Forgot to get Alex’s and Ovid’s score) 8

I don’t know how to apologize: 8 6 2

Please buy only one item: 7 7.5 2

An interesting aside: One thing we hadn’t found out was how Japanese people felt when foreigners laughed at Engrish they thought was funny. When we asked Ai whether or not she felt offended as a Japanese person in such situations, she said no; such humour was 大丈夫. As she put it, most Japanese people don’t know English very well, so it’s expected that mistakes will happen when they try to use English. In this regard, parallels could be drawn to our learning of Japanese: when we communicate with other Japanese students, it is guaranteed that we’ll use broken Japanese with humourous results, yet we won’t feel offended if others find it funny. And while we may feel a bit shy in such situations as we are unaware of our own mistakes, Ai noted that she would feel shy in similar situations when she uses English. However, as Ai assured us, any concern for offense can be dismissed.

Conclusion

Given that humour is deeply influenced by one’s culture, it’s not surprising that for some of the Engrish surveyed here, we got a different response from Ai compared to Alex and Ovid. While Ai did find some of the Engrish humourous after we explained it to her, she noted that if it weren’t for our explanations, she wouldn’t have noticed any humour in the Engrish. Taking this in consideration with the comments received by other Japanese students we’ve interviewed, it may be said that the Engrish that is becoming more pervasive in Japan often goes unnoticed by Japanese people—at least in terms of its meaning. When used in marketing or in fashion, it is meant to give a cooler look, but as Ai’s comments show, not all Japanese people will buy a shirt or enter a restaurant or other shop just because it has English on it. That is, the use of English does not always convey a sense of greater reliability or quality.

More generally, our findings over the past weeks have shown that the Engrish in Japan sometimes offers a distinct reflection of Japanese culture, especially in long-winded, indirect translations that reflect the humble tone adopted by Japanese people when communicating with each other. While the translation may be accurate compared to the original Japanese, it sounds funny to Western ears, showing how cross-cultural communication usually doesn’t work if it’s simply translated literally without considering the cultural aspects inherent in a language.

To everyone in the Senshu program, it’s been a blast! Thanks for reading; now let’s make the most of our last day!